Chronic Stress Test

Published on

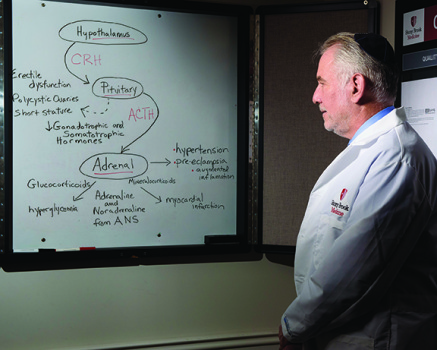

Avram R. Gold, MD, links sleep-disordered breathing to functional somatic syndromes and anxiety disorders via an out of the box paradigm. The iconoclast posits a connection via hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activation, a theory that moves away from commonly held beliefs.

As Avram R. Gold, MD, sees it, the link between sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) and functional somatic syndromes (FSS) and anxiety disorders is evident from recent sleep literature. But the medical director at Stony Brook University (SBU) Sleep Disorders Center does not buy into the commonly held belief that any link must be explained by apneas/hypopneas causing recurrent oxyhemoglobin desaturations and sleep fragmentation.

Instead, the iconoclast presents a very different paradigm in the paper “Functional Somatic Syndromes, Anxiety Disorders and the Upper Airway: A Matter of Paradigms,” published in Sleep Medicine Reviews(2011;15(6):389-401). His theory—that the real link is chronic stress activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis—has earned him both admirers and detractors. Gold, who is also program director of the sleep medicine fellowship at SBU and medical director of the Polysomnographic Technology Certificate Program in the SBU School of Health Technology and Management, insists that with time and the accumulation of evidence, the paradigm will shift. “I have been led toward the ‘chronic stress paradigm’ of sleep-disordered breathing and away from the ‘sleep fragmentation/hypoxemia paradigm’ by the evidence,” he says.

Time for a New Paradigm?

Gold’s thesis states, among patients with FSS and anxiety disorders, inspiratory airflow limitation serves as a chronic physical stress activating the HPA axis, which causes the symptoms of FSS and anxiety disorders as manifestations of the chronic stress.

The paper states that FSS and anxiety disorders share abnormal upper airway function as a common feature, and epidemiologic studies have linked the symptoms of these disorders with SDB. More specifically, studies of patients with FSS and anxiety disorders have demonstrated upper airway dysfunction during sleep. In preliminary studies, normalization of upper airway function has resulted in an improvement of symptoms among FSS and anxiety disorders patients.

Recent sleep literature has acknowledged the link between obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and conditions such as fibromyalgia, depression, Gulf War illness, and anxiety disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Gold says, “For every one of these conditions, there are reports of improvement in symptoms (if not cure) with rapid palatal expansion and nasal CPAP….These two affective disorders and the symptoms of fibromyalgia and Gulf War illness are all recognized by mental health professionals to be associated with chronic stress.”

Perhaps the most compelling argument Gold posits against the sleep fragmentation/hypoxemia paradigm is this: Functional somatic syndromes (including chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, and migraine) and anxiety disorders (including panic disorder and PTSD) are more prevalent in patients with mild SDB (which includes upper airway resistance syndrome as well as mild OSA). That does not make sense using the traditional paradigm, Gold says. Since sleep fragmentation and oxyhemoglobin desaturations increase the more severe a patient’s SDB is, one would expect to see more FSS and anxiety disorders in patients with the most severe sleep apnea, he says.

By contrast, Gold notes that hypopneas and snoring are more prevalent in patients with mild SDB than in patients with severe sleep apnea. How does that relate to the chronic stress hypothesis? While apnea isolates the nasal airway from the hypopharynx and results in nasal pressure that is equal to atmospheric pressure, hypopnea and, to a greater extent, snoring lead to prolonged decreases in nasal pressure. Gold postulates that SDB stimulates the HPA axis through the effect of subatmospheric pressure in the nasal airway on the olfactory nerve. Gold plans to test this olfactory nerve hypothesis in the near future. For now, the olfactory nerve portion of his paradigm is based on the mechanism by which multiple chemical sensitivity is postulated to occur.

Controversy Swirls

Even as Gold’s thesis was published, a commentary in the same issue ofSleep Medicine Reviews challenged Gold’s paper.1 The commentary authors expressed concern about the proposed paradigm’s clinical implications. They said in part, “He implies that millions of people with psychiatric or psychosomatic symptoms or people exposed to disasters or wars… should be evaluated and treated for SDB since it is a major risk factor for these problems or any disorders arising from catastrophic events. Furthermore, Dr Gold suggests that anxiety, panic, OCD, social phobia, PTSD should be treated with CPAP. Such recommendations, if they were to be followed, can have serious adverse consequences. It will have a negative impact on the health of our patients, on our economy and, not least, on the credibility of our field.”Gold published a reply in the same issue.2

Gold tells Sleep Review that the divisions in sleep medicine may be what are contributing to healthcare professionals not associating SDB with FSS and anxiety disorders. Gold says, “Unfortunately, we as a medical discipline have prematurely and artificially divided ourselves into turfs….Now we have behavioral sleep medicine where they focus on things like insomnia, sleep as it relates to psychological or psychiatric disorders, then we have regular sleep medicine where we treat things like sleep-disordered breathing.

“All the people who are in behavioral sleep medicine are not looking at what role sleep apnea is contributing to these psychiatric problems, and in the world of sleep apnea, they’re not thinking, ‘Which of my patients’ psychological problems like depression and anxiety are related to sleep-disordered breathing?’ In fact, it’s a completely artificial separation. The two are very much intermingled.”

In the essay, Gold does note that the understanding of the relationship between FSS, anxiety disorders, SDB, and the upper airway is incomplete. However, by continuing to develop new paradigms and refine existing ones with emerging data and research, an authentic understanding of this association can be attained. Gold says, “The evidence is pointing toward inspiratory airflow limitation being a cause of chronic stress. New paradigms always meet with initial resistance. With time and with the accumulation of evidence, paradigms shift. That process is already beginning.”

Restless Legs Syndrome Link

A clinical implication of Gold’s paradigm that is especially relevant to sleep medicine professionals is the link to restless legs syndrome (RLS), which Gold considers a FSS. Gold has never seen a case of RLS that is not associated with SDB (inspiratory airflow limitation or apnea) and that is not improved with adequate nasal CPAP compliance.

Gold says, “The neurologists think [RLS] is their disorder. They’re putting [RLS sufferers] on dopamine agonists, [patients are] developing augmentation, addictive behaviors, and other complications, and if they just treated them with nasal CPAP, the patients, but not the drug companies, would be better off…and that’s a problem.”

Gold says nasal CPAP is the best treatment option for RLS patients. He says, “If we’re going to treat a patient for sleep apnea, we don’t add pramipexole or ropinirole. We’ll give them the CPAP, we’ll let them use it, and then we’ll see how they’re feeling.”

Daniel Barone, MD, a former sleep fellow of Gold’s and now assistant professor of neurology at Weill Cornell Medical College Center for Sleep Medicine, says, “I think there is a very strong link. For both RLS and periodic limb movements of sleep, I will oftentimes attempt to treat any sleep-disordered breathing either initially or concomitantly with other modalities.”

Clinical Implications

“Increasingly, in the sleep literature, somatic syndromes respond to nasal CPAP,” Gold says. Insomnia patients in particular can benefit from nasal CPAP treatment, he says. “All my insomnia patients have, at a minimum, something resembling upper airway resistance syndrome (UARS). They’re fatigued, they have inspiratory airflow limitation during sleep,” Gold says. “The vast majority of insomnia patients have unrecognized sleep-disordered breathing, and it’s not being treated, and they could benefit from that treatment.”

Gold says that simply using nasal CPAP a few nights a week for at least 4 hours will make a noticeable difference for a patient. “It does not take terribly long for the patients using properly titrated nasal CPAP to benefit, and we have a large population of patients on nasal CPAP levels of 5 cm H2O to 9 cm H2O, the vast majority of our UARS therapeutic levels, doing just fine,” he says.

A full face CPAP mask is another option for the treatment of SDB, but Gold says it may not be the most effective option for patients with FSS or anxiety disorders. He says, “While there is some capability of a full face mask to reduce the amount of obstruction, it takes much higher pressures and it won’t work for the very, very mild sleep apnea patients….I’ve never used a full face mask. When you use a full face mask, and do a CPAP titration, you get very different values for airflow at any pressure, depending on whether the patient’s mouth is open or closed.” Gold recommends the prescription of CPAP by nasal mask or pillows by sleep medicine professionals, saying it is important the pressure go only to the nose and not the mouth.

Importantly, Gold cautions that patients for whom SDB is a chronic stress leading to poor sleep quality recover somewhat slowly after starting CPAP. He says this is because the recovery is a two-step process. First, the airway must regain consistent patency during sleep. Then the HPA axis must calm down, which may take several nights. When patients persist with CPAP—which Gold says his patients do—they achieve decreased stress, which ultimately consolidates sleep.

Impact on Sleep Medicine

The novel paradigm proposed by Gold is new now, but Gold says once the concept is accepted, it may open the door to sleep medicine professionals administering care for patients with an array of conditions. Indeed, at SBU, rheumatologists already send the sleep disorders center a large number of fibromyalgia-patient referrals, as do psychiatrists for PTSD patients. Gold says, “The only danger that I foresee is the danger that the patients being referred will be seen by sleep physicians who do not utilize the tools needed to recognize mild inspiratory airflow limitation during sleep, or discount its role in FSS and anxiety disorders, and do not treat the patients being referred with upper airway stabilization during sleep.”

Alan Schwartz, MD, who has known Gold since they were both pulmonary fellows at Johns Hopkins and is now medical director at Johns Hopkins Sleep Disorders Center, director of the Sleep Medicine Fellowship program, and co-director of the Center for Interdisciplinary Sleep Research and Education, says, “It’s an idea that sleep medicine needs to begin to embrace. It is not necessarily typical of current practice that we see that sleep practitioners are automatically seeing the connection between sleep-disordered breathing and a whole spectrum of disorders.”

In addition, Schwartz says the acceptance of this new idea may have broader implications in the field. Schwartz says, “If sleep medicine professionals embrace this concept, then they will begin to realize that sleep medicine is applicable to the diagnosis and management of potential triggers for a broad range of disorders. The overall affect will be that this concept will tend to broaden the field of sleep medicine tremendously and extend our purview into the diagnosis and management of functional disorders and a group of disorders that are loosely collectively called functional somatic syndromes.”

Future Research

For future research into this proposed paradigm, Gold says that presently his research team has not sought out an opportunity for a large study on these affective disorders and somatic syndromes. Presently, Gold would like to test the olfactory nerve hypothesis as well as examine other life-threatening disorders that he thinks are associated with SDB. In addition, Gold is coauthoring the chapter on snoring and upper airway resistance syndrome in the sixth edition of The Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine together with Riccardo Stoohs, MD, of the Somnolab Sleep Disorders Center in Dortmund, Germany, which will explore the proposed stress hypothesis. Gold says this is “another indication of how the paradigm is beginning to shift.”

Schwartz says the kinds of studies Gold has conducted at SBU School of Medicine should be extended to multiple centers and have a broader range or number of patients involved. This expansion will help to gain a greater understanding of this medical concept. Schwartz says, “People [will] develop a greater confidence in the findings and so we, as sleep practitioners, begin to understand the overall generalizability of his findings as well. I also believe that physicians whose primary practice does not involve sleep medicine will need to gain greater awareness that there is a link between sleep-disordered breathing and functional somatic syndromes.

“I think there are a number of medical specialty areas that would benefit tremendously from knowledge and greater understanding of the connections that Dr Gold is pointing out.”

Gold says, “The reader can consider my review as a collection of the findings suggesting that unrecognized SDB plays an etiologic role in the FSS and anxiety disorders. These findings, together with a new paradigm of SDB to explain them, can be used to justify the larger, controlled studies that will come in the future.”

Future Clinical Implications

According to Gold, the biggest obstacle health professionals may face when treating FSS, anxiety disorders, or depression with sleep apnea treatment will be that they are “cutting in on territory that other medical subspecialties or psychologists consider their own.” Gold says, “There’s nothing that says [patients] can’t continue to have their treatments with their other physicians. By treating them with nasal CPAP or an oral appliance, you may still be improving the level of their symptoms beyond what they’re getting from other approaches. I think that’s an important thing to consider.”

Barone says this new idea is wholly supported by current sleep-centered research. Barone says, “I think these ideas are completely congruent to what is being found in our field as time goes on. From the recent literature purporting insomnia to actually be a 24-hour disorder, to the finding that sleep-disordered breathing occurs in many patients with insomnia, to the link between heart rate variability changes and sleep-disordered breathing, I think all of these have connections to the ideas of upper airway resistance and flow limitation as described by Dr Gold….I hope that it becomes more recognized in the field, from both a diagnostic and therapeutic perspective.”

Schwartz says, “The connection between functional disorders and sleep-disordered breathing problems is really a new one. Dr Gold’s contribution to the field is that he has provided compelling data to suggest that, in fact, there is a link between sleep-disordered breathing and a variety of functional disorders.”

In the future, we can expect more published papers from Gold—and likely more controversy. Time will tell if Gold’s paradigm holds up to increased research and scrutiny. But Gold has no doubts. He says, “I know that tomorrow, SDB will be recognized to have a pathophysiologic role among disorders where knowledge of its presence is ignored or resisted today.”

Cassandra Perez is associate editor for Sleep Review. CONTACT cperez@allied360.com

Caption for topmost image: Gold’s theory incorporates the relationship between the metabolic manifestations of chronic stress and the hormones associated with the HPA axis.

REFERENCES

1. Vgontzas AN, Fernandez-Mendoza J. Is there a link between mild sleep disordered breathing and psychiatric and psychosomatic disorders? Sleep Med Rev. 2011;15:403-405.

2. Gold AR. There is! Sleep Med Rev. 2011;15:407–409.