Why It’s Harder To Sleep As We Get Older

- ERIN BRODWIN

/ OCT. 7, 2014, 2:33 PM

She makes it look so easy.

Sleeping helps us process memories, learn new skills, and stabilize our mood. Yet as we get older, a good night’s sleep becomes a rare commodity.

Scientists have struggled for years to find out what makes sleep more elusive as we age. As it turns out, there are a number of factors that change how — and when — we sleep, from shifts in brain activity to a loss of special brain cells that tell us when it’s time to rest. And not getting enough shuteye, no matter our age, can have dangerous repercussions.

Here’s what happens to our bedtimes as we age.

Goodbye, Deep Sleep

As we get older, we tend to get slightly less sleep, and the quality of that sleep is poorer, with more awakenings throughout the night. Our brains also spend fewer hours in deep sleep mode, that precious time when the frantic chaos of brain activity grinds to a slow burn. During deep sleep, or slow wave sleep, our brain waves stretch out and get less frenetic.

A typical 25-year-old plunges half a dozen times into several hours of sustained deep sleep throughout the night. In contrast, the average 70-year-old brain shuffles quickly in and out of moderate-level sleep, spending only a few minutes in the deepest phase of rest and far more time in shallow sleep or complete wakefulness. The transition between being asleep and awake also becomes far more abrupt as we age. This is probably why older people are generally more likely to call themselves “light sleepers.”

Unfortunately, our changing sleep patterns have some pretty stark effects on our health and cognitive functioning.

For starters, not getting enough deep sleep messes with our memory. When we hit deep sleep, our slowed-down brain waves help transfer short-term memories stored in the hippocampus to our prefrontal cortex, where they are recorded as long-term memories. But when we don’t spend much time in deep sleep, a recent study study suggests, our newest memories can get stuck in the hippocampus, where they are soon overwritten with new memories.

Hello, Afternoon Nap

In the 1990s, scientists identified a tiny section of the brain that acts as an on/off switch for sleep in mice. Earlier this year, the same team of researchers discovered that humans have a sleep section of the brain, too, and that as we age, we lose the special type of brain cells that live there.

After making this initial discovery, the researchers took a look at the data from a long-term sleep study of more than 1,000 people who joined at age 65 and agreed to be monitored until their deaths. The scientists found that people who lost a larger number of these brain cells had more fragmented sleep patterns — they woke up more and slept for shorter periods. The relationship between the cells and sleep patterns was surprisingly precise: The fewer cells someone had, the more disrupted her sleep. The more disrupted someone’s sleep, the worse their memory.

Our answer to our broken-up cycle of unsatisfying sleep? Naps.

Typically, naps still don’t allow us to reach deep sleep, but they do help make up for the decreases in alertness and increases in stress that can result from too little shuteye.

A Lifelong Trend

You might not remember it, but your parents sure do: From the moment they brought you home from the hospital as a newborn, you never slept for more than a few hours at a time.

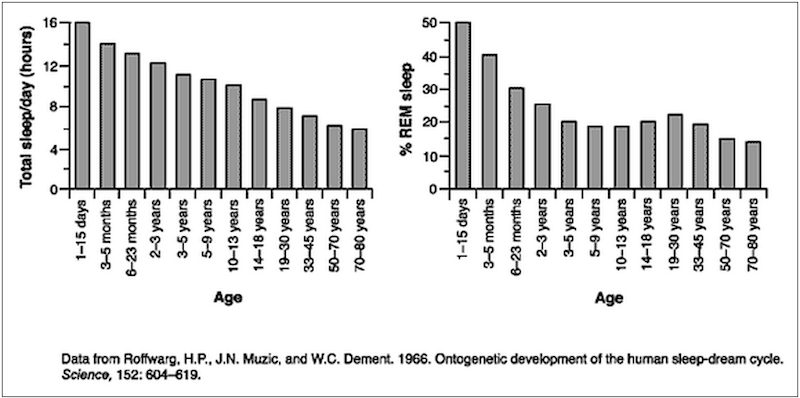

Yet even after managing to wake them up throughout the night, your infant self clocked in up to 20 hours of sleep each day. By the time you celebrated your fourth birthday, you cut back your daily shuteye to 12 hours, and as a teenager, you slept a conservative 9 hours each night.

In keeping with this gradual trend, the average 35-year-old gets about 8 hours of shut-eye each night. By the time we hit 70, most of us need only about 7 hours. Older people also get far less REM sleep.

The difference between a 70-year-old’s sleep schedule and a 35-year-old’s, however, is that older people rarely get all that sleep in one solid block, leaving them groggier after waking. Hence the afternoon nap.

Lost Sleep Is Not Always Due To Age

In the elderly, difficulty sleeping could also be a side effect of other problems like muscle spasms, depression, anxiety, and respiratory disorders like sleep apnea, which becomes more common as we age.

These are often treatable conditions that can go undiagnosed when people assume sleeping problems are simply a natural byproduct of old age. Other chronic conditions, such as arthritis, can disrupt sleep, so it’s important to make sure these issues are not simply dismissed as run-of-the-mill insomnia.