Up all night: all about insomnia

James Evan Bowen-Gaddy / Staff Writer

December 12, 2016 – PittNews.com

Kelly Shaw is lying in bed, staring at the ceiling and wondering why she’s so tired, but she can’t sleep. At this point she’s just a third-grader, so she asks her father what to do. He tells her he bets she can’t count to 2,000 before falling asleep, so she takes him up on it.

“It worked the first couple of nights,” Shaw said. “But once you start getting to 2,000, the counting isn’t as effective.”

Shaw, now a senior at Pitt studying psychology and sociology, has given up on counting to high numbers to fall asleep these days because she knows it won’t work. She’s a self-diagnosed insomniac.

According to Pitt researcher and UPMC sleep expert Dr. Peter Franzen, 10 percent of the population is affected by insomnia, defined as “difficulty sleeping despite adequate opportunity.” Franzen said a clinical diagnosis of insomnia is less common, but many people have insomnia symptoms, such as trouble sleeping and daytime drowsiness. When it becomes a chronic problem, he said, patients begin to call it insomnia.

“What we know is that insomnia is really common,” Franzen said. “Everybody is going to suffer from some nights of insomnia at some point in their life. Whether it becomes a consistent problem, and then you could say have an insomnia disorder — well, that’s a different story.”

College students, including Shaw, can be seriously affected by it. He stressed, however, that many students are typically victims not of insomnia but of sleep deprivation, a more conscious choice that can be avoided.

“Those are two very different things,” Franzen said. “Sleep deprivation [is when] you’re not getting enough sleep, but you could if you just tried. Insomnia [is when] you have an adequate sleep opportunity — you just don’t get enough sleep.”

After so many years of battling insomnia, Shaw said she is tired of having restless nights.

As a child, she asked to go to “night school.” In college, she has adjusted her work schedule to fit into her long nights, often staying up all night at least once per week and using that time to catch up on school work.

She said it’s much easier to get things done when no one else in Oakland is awake, letting her stay focused. It’s only when the sun comes up that she’s reminded this isn’t normal behavior.

“There’s been a lot of times where my roommates come down during what’s morning for them, and I’m just like, ‘Oh sh**, the world’s awake now,’” Shaw said.

Franzen said this kind of behavior is not recommended or healthy for students trying to learn, however. Studies show that sleep deprivation affects not only mood but also memory and motivation.

More than once, Shaw said, her sleep impairment has seriously worried her. Once, as she studied for an exam after two sleepless nights, she began to hallucinate.

“I was just looking at PowerPoint printout notes, and there was this colored blob that was forming in the middle of the page and moving,” Shaw said.

Although insomnia can start for many reasons, including illness, chronic pain, stress, side effects of medications or depression, Franzen said it often spirals into a “chronic insomnia that maintains itself.”

Because of this, Franzen says a strong treatment route is behavioral interventions, which focuses on changing habits that could be causing insomnia.

“People might think they want to lay in bed and be resting, but what you’re doing is just training your body to say, ‘When I’m in bed, I’m going to be frustrated and awake,’” Franzen said. “You want to break those associations and know that when you’re in bed, you’re going to be sleeping.”

With one study from June 2016, Franzen and a team of researchers found that having a sleep diary could improve sleep. The subjects, students from Carlow University, kept track of when they went to bed, when they woke up and how many times they up each night. Franzen said that even though they didn’t have a control group — a requirement for claiming causality — they were still surprised to see many of the students’ sleep improve.

The other method towards solving insomnia is pharmacological treatment — drugs like Ambien, Lorazepam or Lunesta.

Harpreet Bassi, a Pitt senior studying biochemistry, has battled insomnia symptoms intermittently since high school and consistently since her sophomore year of college, and has attempted to take melatonin supplements as a treatment. She’s also tried stronger treatments like diphenhydramine HCl, a non-habit-forming and non-prescription drug, but she saw little benefit to taking either drug.

She said the one chemical that can help is alcohol.

“Drinking nights are great,” Bassi said. “The alcohol puts you to sleep. Some nights I just go to bed a little earlier, [but] I’m still going to bed at 3, 4 a.m.”

Franzen said many college students believe this to be true but that alcohol is actually detrimental to healthy sleep.

Since alcohol is a strong hypnotic, it will easily help aid someone in falling asleep. This doesn’t last, however, because once they starts withdrawing from the alcohol, their sleep becomes much lighter.

“You might have an easier time falling asleep, but you’ll have a harder time throughout the night,” Franzen said.

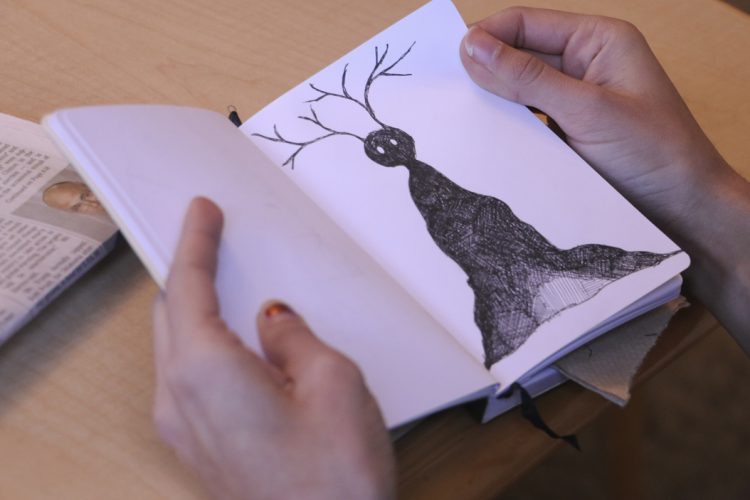

When Bassi isn’t trying to treat her insomnia, she’s reading or drawing. The activities she likes to do during the day feel better than simply lying in bed doing nothing.

“My night drawings are a lot better,” Bassi said. “Just more detailed. I guess I have more time where I’m not doing anything [else].”

Even though this gives Bassi a few more hours to work at night, she finds the effects of sleep deprivation during the day erratic.

“Sometimes, if I haven’t slept a night, I’m super loopy the next day, and that’s kind of one of the best feelings,” Bassi said. “Just like, ‘Whoa, everything seems unreal.’ The high without the drugs. Other times I’m so tired, I don’t want to talk to anyone.”

Shaw echoed this feeling of elation that can come about the next day. She said if she’s pulled an all-nighter, she’s hit with a rush of energy around 8 a.m.

“I’ve definitely experienced a mental crash where my brain turns off but my body keeps moving, and it’s weird, but there’s something kind of enjoyable about it,” Shaw said.

Although Shaw takes melatonin pills, she said she’s not really interested in trying any other treatments since the extra time has become necessary to her work schedule.

“I hit the point where I started accepting it and working with it,” Shaw said. “I’ve made it my thing, and — I’m not going to lie — sometimes I take a little bit of pride in it.”